“Anti-cultists” sometimes accuse religious groups of committing child abuse or human trafficking. But the story we tell here reveals that some leading representatives of the “anti-cult” movement may themselves be guilty of horrific crimes involving children. And their colleagues are culpably silent.

“Anti-cultists” sometimes accuse religious groups of committing child abuse or human trafficking. But the story we tell here reveals that some leading representatives of the “anti-cult” movement may themselves be guilty of horrific crimes involving children. And their colleagues are culpably silent.

The case of the Southern Cottage (Casitas del Sur) came to light in 2008, when young teenager Brenda Bernal Hernandez escaped from the shelter “Refugio de Amor” located in the municipality of San Nicolas de los Garza in the Mexican state of Nuevo Leon.

When the girl recounted a horrifying story of her experiences in the shelter, the authorities were forced to look into what was happening in these alleged “Christian shelters” that turned out to have nothing whatsoever to do with any Christian Church. They were instead a criminal enterprise hiding behind the name “Christian.”

What was found: a network of 40 similar shelters used for child trafficking and distributed throughout the Mexican Republic from which more than 25 minors “disappeared.”

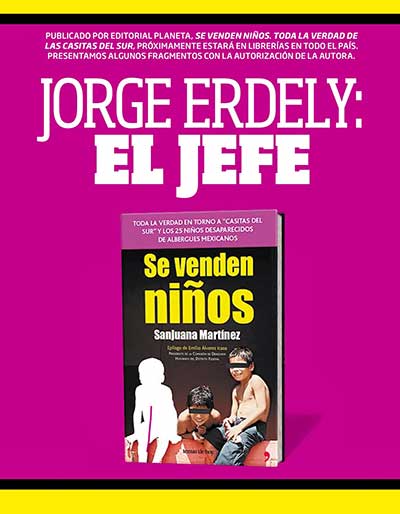

The story was covered extensively by an investigative reporter from Mexico, Sanjuana Martinez, who wrote a series of articles and published a book, Children for Sale [Se venden niños]. Mexican authorities investigated the matter which resulted in raids and at least seven arrests.

The story was covered extensively by an investigative reporter from Mexico, Sanjuana Martinez, who wrote a series of articles and published a book, Children for Sale [Se venden niños]. Mexican authorities investigated the matter which resulted in raids and at least seven arrests.

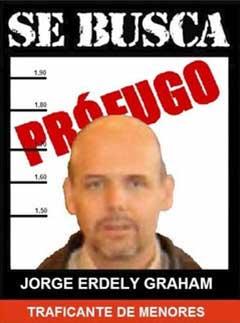

These “shelters” for children were established in 2000 by Jorge Erdely Graham. While this name may not seem familiar to our readers, it was definitely a name well-known among so-called “anti-cult” activists—until 2009 when his name became a burning liability to his former confederates. Creating a façade as a “protector of the faithful and kids abused by cults,” he in fact created his own cult as a cover to run a network of child trafficking, literally selling kids for sex and even organs.

Jorge Erdely was not just a member of ICSA (International Cultic Studies Association, a U.S.-based front group for the anti-religious movement) and AFF (American Family Foundation, the former name of ICSA), he was a member of the ICSA board of advisors and a regular guest speaker at ICSA annual conferences.

Jorge Erdely was not just a member of ICSA (International Cultic Studies Association, a U.S.-based front group for the anti-religious movement) and AFF (American Family Foundation, the former name of ICSA), he was a member of the ICSA board of advisors and a regular guest speaker at ICSA annual conferences.

In 2009, when Erdely became a fugitive from the Mexican justice system, ICSA quickly and quietly removed his name from all their literature and websites, apparently hoping that expunging any and all mentions of Erdely would cover up his past prominent association with the organization.

While Erdely’s name and story were high profile in Mexico from 2008 to 2014, the story didn’t make the media in the U.S or Canada, even though Erdely had fled to those countries to evade authorities in Mexico. Media silence reigned in Europe as well, even while Mexican media was reporting that Erdely was setting up “shelters” in Europe and Thailand.

When Erdely had established his “Restored Christian Church” in Mexico in 2000, he carefully omitted his name from appearing anywhere as the legal representative of the trafficking front. He tried to shield himself with three others: Antonio Domingo Paniagua Escandon, Sixtio Garcia Castaneda and Alberto Burgos Licona. Investigation, however, revealed that Erdely was not only the mastermind behind this “church,” but “A Spiritual Dictator,” according to an article of March 31, 2009, in leading Mexican newspaper El Universal.

When pressure from police started to close in on Erdely’s enterprise, some “disappeared” kids all of a sudden started to reappear, released a few at a time. It is not known how many are still missing. In 2014 there were eight identified children missing and as of 2020, there is no evidence they ever returned despite large money offered by the authorities for information about the missing children.

Before the scandal erupted, Erdely embarked on a step-by-step scheme to build a false reputation for himself as a “cult expert.” He formed his own civil association, Centro de Investigaciones de Instituto Cristiano de Mexico [Investigation Center of the Mexican Christian Institute], wrote several books and enlisted support from religious scholars including Elio Mansferrer and Cesar Mascarenas. He appeared on Televisa, one of Mexico’s biggest TV stations, as a “cult expert.” He maneuvered himself into position to benefit from gaining the ear of government people to espouse anti-religious invective and to receive various forms of monetary support from municipal, state and federal government agencies.

Ostensibly overseeing Erdely’s “shelters” was the DIF—the National System for Integral Family Development [Sistema Nacional para el Desarrollo Integral de la Familia; SNDIF or just DIF], a public social assistance agency. Reporter Sanjuana Martinez calls DIF “one of the worst Mexican institutions, without transparency and whose budgets are mainly used to provide food in times of elections as well as for the personal affairs of the First Lady—supposedly supervised the hostels of Jorge Erdely Graham and authorized the transfers of minors at risk.”

Ostensibly overseeing Erdely’s “shelters” was the DIF—the National System for Integral Family Development [Sistema Nacional para el Desarrollo Integral de la Familia; SNDIF or just DIF], a public social assistance agency. Reporter Sanjuana Martinez calls DIF “one of the worst Mexican institutions, without transparency and whose budgets are mainly used to provide food in times of elections as well as for the personal affairs of the First Lady—supposedly supervised the hostels of Jorge Erdely Graham and authorized the transfers of minors at risk.”

What the children found in these shelters was atrocious indoctrination, physical abuse, labor and sexual exploitation and even organ trafficking, according to Martinez’ 2010 book Se venden niños [Kids for Sale], in which she details conspiracies between authorities and traffickers of children.

Erdely and the other leader of the organization, Sergio Humberto Canavati Ayub tried unsuccessfully to stop publication of the book, using a high-priced New York law firm to issue threats of filing criminal complaints if the book was not withdrawn. The publisher did not back down and the book was released.

With a child trafficking network in other countries by this time, Erdely and Ayub continued their attacks on the reporter. They got articles published in the Mexico City newspaper La Jornada and El Norte, a daily paper in Monterrey, Nuevo Leon, Mexico, seeking to discredit Sanjuana Martinez’ work. They demanded the right of reply to another Mexican journalist after a CNN interview they didn’t like.

The reporters carried on, however, and further investigation found that the children’s shelters also operated in Thailand, in European countries and in South America.

Quantifying the number of children swept into the “shelters” and disappeared is difficult if not impossible to estimate. Many of the victims were picked up off the streets and had no identification of any kind, and certainly not a birth certificate.

The 10-year-old Ilse Michel arrived at the Casitas del Sur shelter in 2007 by order of the PGJDF (Attorney General Office of Mexico City) as an alleged victim of domestic violence. In 2008, the authorities granted parental authority to her grandmother, but the shelter refused to release the child. This and other complaints caused Emilio Alvarez Icaza from the Human Rights Commission of the Federal District to go to the shelter in January 2009 to inspect firsthand.

Monterrey and Cancun prosecutors were receiving similar reports of minors disappearing from Erdely’s network of shelters. PGR [Attorney General Office] launched an investigation which 10 years later is not completed.

On 1 June 2010, Antonio Domingo Paniagua Escandon, nicknamed El Kelu, was arrested in Spain and extradited to Mexico the following year. The judge considered that as private secretary to Erdely, Escandon would have knowledge of and likely participation in decisions and actions related to the trafficking of minors.

Braulia Valverde Vilchis, who was in charge of Casitas del Sur, was arrested in 2012 for his part in the child trafficking operation. Seven individuals connected with the network have been arrested, but the principals are still at large.

And worse, as of 2020 children are still missing and it appears that no one is looking anymore. The question then is why has the Attorney General’s Office failed to arrest Jorge Erdely Graham and Sergio Humberto Canavati Ayub?

Erdely was known to be in Canada and New York, from where he even offered an exclusive interview for major Mexican newspaper El Universal. Ayub was reportedly in charge of the “shelter” in Thailand and his official residence is in Monterrey.

It appears that authorities at some point ceased to make efforts to pursue the investigation and bring these two criminals to justice.

Among other unanswered questions: What did the International Cultic Studies Association—ICSA—know about its poster boy Jorge Erdely Graham and when did ICSA know it? Why didn’t ICSA talk about this horrific crime at their conferences? Isn’t this an actual cult they should be concerned about and working to protect the public from its dangers?

The International Cultic Studies Association web page states under the title:

“Helping People Since 1979” and among other things they provide information on “abusive churches.” Yet in this case, ICSA has failed over many years to provide any information on Erdely Graham’s cult masked as a church.

And what about FECRIS, the France-based European Federation of Centres of Research and Information on Sectarianism, which like ICSA is a front group for antireligious activity. Among the stated objectives of FECRIS:

And what about FECRIS, the France-based European Federation of Centres of Research and Information on Sectarianism, which like ICSA is a front group for antireligious activity. Among the stated objectives of FECRIS:

“Alert public authorities and international institutions in the event of punishable activities:

“Create an international information network.”

And from their declaration of intent:

“To make available free information to enable individuals to protect themselves against the adverse practices of sectarianism” which comes after a false assertion that FECRIS supports the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

If FECRIS and ICSA are true to the above objectives, they should provide information on the whereabouts of Erdely Graham and help bring him to justice.

Will FECRIS and ICSA stop ignoring (or covering up?) this matter and come forward and provide any and all information in their possession on Jorge Erdely Graham and his accomplices so that the Mexican authorities can finally bring these people to justice?

We will continue to probe for answers to these questions and will update our site with new information as we uncover it.