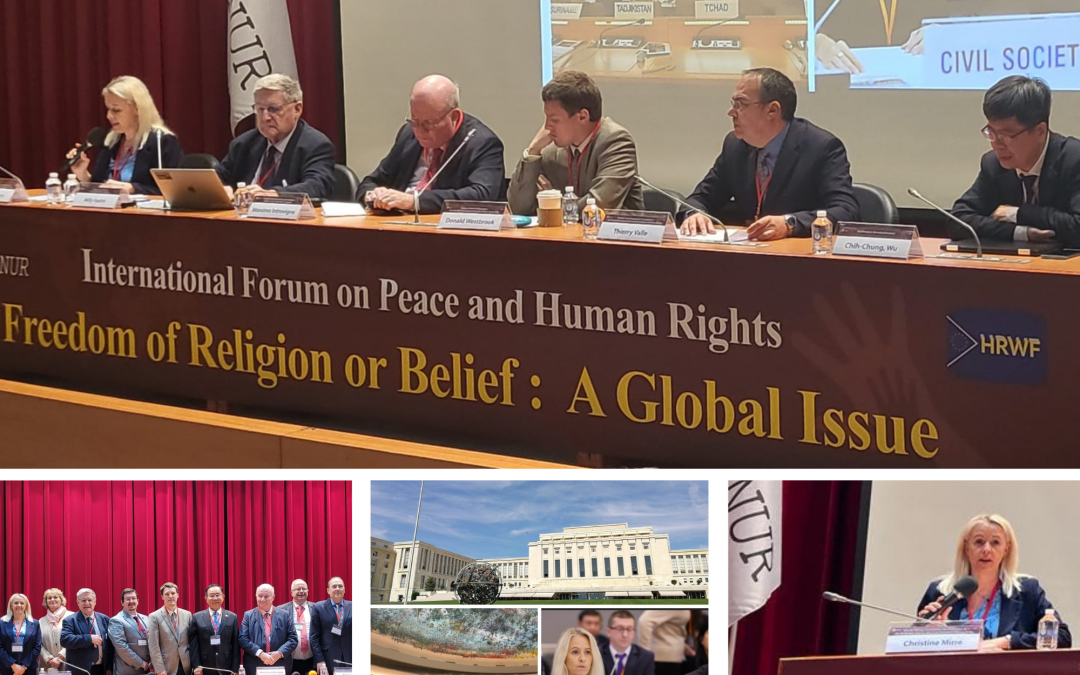

International Forum on Peace and Human Rights

Freedom of Religion or Belief: A Global Issue

April 9, 2023

Conference Hall of Tsai Lecture Hall, College of Law, National Taiwan University

by Christine Mirre – 09/04/2023

History of the Civil Society Power at the United Nations

The prejudice suffered by the Tai Ji Men for more than twenty years must be denounced to the international community and to international institutions such as the United Nations, so that the international community may urge Taiwan to cease its persecution and comply with international human rights standards.

In this process, the role that civil society can play is essential and to better understand it, we will look into its history and its influence on international institutions, particularly the United Nations.

Contrary to the common belief that civil society is a recent notion, the powerful instinct that pushes citizens or members of a same community to gather to defend a cause or to fight against inequity has its roots far back in time.

Civil society has proven in the past, its ability to change things, to overturn diktats, and this, always in the perspective of a betterment for a group or for the whole of humanity, in a presumed consciousness of the human rights inherent to Man, that have since, been expressed in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

The term “civil society” is commonly defined as the set of non-profit movements and associations, independent of the State, whose aim is to transform, through concerted efforts, social policies, norms or structures, at the national or international level.

The United Nations defines it as the “third sector” of the society, alongside government and business. It includes civil society organizations and non-governmental organizations. The UN takes an optimistic and positive view of civil society, considering that it can advance the ideals of the UN.

Today, civil society and non-governmental organization (NGO) are synonymous terms and are equally used.

The notion of civil society has its roots in Western political philosophy and goes back to Greek and Latin Antiquity.

In his writings, the Ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle uses the expression “koinônia politikè” which translates in Latin as “societas civilis” meaning a “politically organized community of citizens” that is distinct from family or people.

Religious orders are by far, the most numerous of the ancient forms of NGOs and some still survive today. Although its records only go back to the 16th century, the oldest is probably the Sovereign Constantinian Order.

The variety of what we call NGOs today was composed of institutions such as religious orders, charitable organizations, missionary societies, brotherhood societies, merchant associations…

Religious orders are notable for the crucial role they play in the development of horizontal relationships between people in different contexts before the emergence of the public sphere.

On the Eastern side, the first civil society in China may date back around the years thirteen hundreds. The earliest known is the Chinkiang Association for the Saving of Life, which is said to have been established in 1708.

During the French Age of Enlightenment in eighteen century, civil society was seen as a well-ordered and secularized society, formed to raise its voice and resist both state and religious authoritarianism.

During the 19th century, NGOs deal with issues such as the fight against slavery, art, cooperation, education, the rights of indigenous peoples, peace, women’s emancipation, etc.

After the First World War, NGOs became more interested in practical actions. It is to be noted that civil society had a significant impact on the Paris Peace Agreement, and on the creation of the League of Nations in nineteen twenty. At that time, the NGOs were more influential, for example in the development of the Dawes Plan, which resolved the issue of World War I reparations that Germany had to pay.

As Paul LOWENTHAL notes in his book in 2005 “Civil Society and Political Participation, the Traditionally Shared Vision”, “from Machiavelli to Gramsi to Rousseau to Hegel and to Marx, political philosophy defines civil society as all that is not the formal political society.”

We can see that organizations entirely dedicated to a particular fight appeared at the end of the eighteenth century and take an international dimension in the 19th century.

By the end of the nineteenth century, habits of cooperation had developed in international public action. As one contemporary commentator explained, “Governments sometimes took the initiative, but it is not too much to say that, in most of the forms taken by their international actions during the nineteenth century, they followed, hesitantly and reluctantly, a path laid out by others. “

In the background of many intergovernmental bodies, there were active and idealistic NGOs. Politicians appreciated their input. Official government representatives were not shy about sitting with them at international conferences. So, NGOs discovered at that time that they could influence governments. They left their imprint on new conventions dealing with the laws of war, intellectual property, maritime law, prostitution, drugs, labor, and wildlife protection. And when general multilateral conferences were held, NGOs invited themselves to the negotiation table.

It was during this period that they began to realize their importance, as illustrated by the creation of the Union of International Associations in 1910 and that they increasingly participated in international governance.

This is particularly true in the field of environment, where they regularly take part in multilateral conferences and monitor the development of treaties. They are also increasingly active in the World Bank and in human rights agencies.

The growing role of NGOs in international politics and legislation is a significant development. Their positive influence can be seen in the early years of the League of Nations.

Then, even more NGOs promoted a new international organization to replace the League of Nations in the post-war era.

Since the United Nations creation in 1945, NGOs have interacted strongly with it.

Specialists such as Tony Hill of the United Nations Non-Governmental Liaison Service, in his article of April 2004: “Three Generations of UN-Civil Society Relations”, speak of three generations of NGOs.

The first generation of NGOs played an important role in the evolution of UN standards and policies, beginning with advocating for the inclusion of human rights in the UN Charter in 1945 and the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Also in 1945, government representatives recognized the need to involve non-state groups operating at the international level in the work of the future UN.

In San Francisco, delegations from 50 states agreed to include Article 71 of the Charter, I quote: “The Economic and Social Council may make suitable arrangements for consultation with non-governmental organizations which are concerned with matters within its competence” thus rephrasing “the third UN”, the term for civil society in UN jargon, the first two UNs consisting of the member states and their delegations for the first, and the UN secretariats and offices for the second.

They not only successfully advocated for a strong anchoring of the idea of human rights in the Charter, but also succeeded in getting Article 71 included, enshrining the right of civil society to be present and consulted on UN matters.

This first generation of NGOs, which lasted until the end of the Cold War in the late 1980s involved mainly International NGOs (INGOs) of different varieties, including professional and trade associations that benefited from formal consultative relations with the United Nations, which is the origin of the acronym ECOSOC (Economic and Social Council)

The NGO Committee was established in 1946 along with the General Assembly, the Economic and Social Council, the Security Council, the Trusteeship Council, the International Court of Justice and the UN Secretariat.

The Human Rights Council is a subsidiary body of the UN General Assembly.

The Cold War, which shaped the UN’s intergovernmental deliberative processes, also had a significant impact on the dynamics and role of INGOs at the UN.

Of note is the involvement of civil society in the deliberations at the Stockholm Conference on the Human Environment in 1972 and in the work of the International Coalition for Development Action (ICDA) at the North-South Dialogue for an INGO (under the auspices of UNCTAD) in the 1970s-80s.

Overall, however, the relationship between the UN and the first generation of NGOs was more formal and ceremonial than political.

This is not to say, that the role of INGOs in the first generation of UN-civil society relations was unimportant or inconsequential, far from it. It brought many new ideas and produced eloquent spokespersons to the work of the UN.

Above all, it established the right of non-governmental actors to participate in UN deliberations and gave real and practical expression to the possibilities opened up by Article 71 of the UN Charter.

And although this desired collaboration between the UN and NGOs, let’s be honest, has often been a rocky road, the idea of including civil society in UN policy discussions – as relevant today as it was in 1945 – would probably not have been introduced without the efforts of the early actors of the third UN who secured a seat at the table for the civil society.

This form of official recognition of NGOs and the institutionalization of their participation in the multilateral functioning has led to a considerable increase in the number of NGOs in relation with the UN: in 1950 there were only 50 NGOs accredited to the UN, in 1995 there were 1000, and in the year 2020 there were 5500.

The end of the Cold War and the decisions by the UN to commit to a series of major global conferences and summits throughout the 1990s marked the beginning of a second generation of NGOs whose nature of relationship with the UN was different.

Indeed, a large number of non-governmental actors, particularly national NGOs from developing countries, the Western Hemisphere, and, although to a lesser extent, post-communist societies in Central and Eastern Europe, emerged around the major UN conferences on environment and development, human rights, women’s rights, social development, human settlements, and food security.

This second generation was able to take an active part in the preparatory and follow-up processes of these conferences.

To describe the relationship of the third generation of NGOs with the UN, I would quote Mr. Kiai MAINA, former UN Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and association: On 2016 he said: “In today’s globalized environment, democracy stretches beyond national boundaries, and the United Nations is an arena where some of the world’s most significant political decisions are made. Ordinary people, though civil society organizations that may have a different view from their government, must have a voice in this process, particularly when they can barely speak out at home. The United Nations has a responsibility to give them that voice.”

The new feature of this third generation of NGOs is the emergence of “small” NGOs, but the crucial contributions of these smaller and less visible NGOs have been instrumental in shaping standards on issues such as the environment, indigenous peoples, women rights and peace.

For example, the origins of Resolution 1325 and the Women, Peace and Security Agenda lie largely in the lobbying efforts of small NGOs and civil society groups to get member states and UN bodies to recognize the impact of war on women and the women’s contribution to conflict mediation and peacebuilding.

Although they have far fewer resources to access the front door of policy discussions, they have found ways to access the back door and even break the front door as in the case of resolution 1325.

Eleanor Roosevelt, the very mother of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, was so right with her “diplomacy from below“.

She campaigned for the voice of civil society to be heard, voicing the demands of civic associations and ordinary citizens, and successfully advocated for civil society to have a seat at the negotiation table.

In conclusion, History has shown that the civil society, in its various forms, has always played an important role in the organization of human society and has been able to advance great causes for a world betterment.

This look into the past restores hope for the future, it reminds us that with commitment and persistence everything can be accomplished.

Today, all of us gathered here in Tai Pei for this symposium with our different backgrounds and specializations (as scholars, lawyers, experts, human rights defenders), we are raising our voices as representatives of the civil society to make the cause of the Tai Ji Men and the injustice they suffer heard by international community and institutions and to ensure that it ends up.